|

| J. Ray Shute - first row, 2nd from right circa 1918 - Heritage Room Photo Collection |

1982 Interview by Wayne Durrill

What was it like growing up in Monroe?

"It was very pleasant. It was a good town to grow up in. Life was slow and easy, friendly. There were no social problems that were of any significance, and there was no bustle and hurry of the larger city. Everybody knew everybody, and life was good. People trusted each other, and the little spats that the womenfolk quite often would have, and some men, as a rule didn't amount to too much. They were not too serious.

"We played a lot of games. Baseball was quite popular. We hadn't graduated into tennis yet—that came later—but horseshoes, buckety-buck, all sorts of games and things. Later, outdoor basketball in the schools. We had courts outdoors; they didn't have any gymnasium back in those days. Some track, but that was usually an annual event in the spring of the year, and all the county schools would participate in track meets. They were well attended, too.

"But as a young boy, we shot marbles and had tops and things like that. We didn't have any mechanical toys to speak of like trains and things. We had trains, but they were cast iron; the wheels didn't turn. It was just something to look at, you might say. Had that sort of toys. But the tricycle was an important vehicle that the more affluent families could afford to buy for their children. Nearly all the boys in our neighborhood had tricycles that we'd ride, and the girls could ride them, too. Then later on, as you got older, the bicycle itself came along, so you were getting along when you got a bicycle that you could ride to school. Everybody wanted to ride it. Life was easy, gentle, and friendly. No evidence of discrimination and segregation, as we envision them today.

"My home was on the corner of Church and Talleyrand—it was called Bryant Street then—but I spent nearly as much time in the home of our cook, who had boys my age. We'd slip off and go swimming together. Never thought anything of it until after we got into school, and the teachers told us it was wrong. I often wonder what would have happened if they hadn't paid any more attention to it than we did. I don't think we ever would have had any racial problems. And the same way with trains. This Jim Crow business was a latecomer, too. You didn't use to have that. You didn't have areas segregated black and white and this, that, and the other in the early days. The idea of segregation, I think, was more of a northern phenomenon than it was southern. Eventually, it came here, too.

"But coming back to the other part of it, everybody went to church, men, women, and children. We also went to Sunday school. We also went to prayer meeting on Wednesday night, and they usually had pretty good attendance. You see, there was so little to do in the way of entertainment.

|

| Opera House - Heritage Room Photo Collection |

|

| 1912 Parade - Heritage Room Photo Collection |

"The Fourth of July was the big day of the year. We didn't shoot firecrackers much at the Fourth of July; we did that at Christmas. But we had firecrackers. T. P. Dillon always was chairman of the committee to run the Fourth of July. He'd have fireworks that night. But that's when we had the big local parade, and they were fantastic, too. It had every category you could think of: bicycle competition, floats, bands, and just every sort of thing. The parades would be long, and everybody in the county would come to Monroe to see the Fourth of July parade. You just wouldn't dare miss that. We'd look forward to that for months. But it was pleasant. We didn't have much, but we didn't require too much, and it was all right.

"Monroe Graded School was set up in 1900. We had a boarding academy here before that. They had a fire, and I think three of the students were burned to death. I went through graded school and two years of high school. Then I went to Georgia Military Academy, and I graduated down there.

|

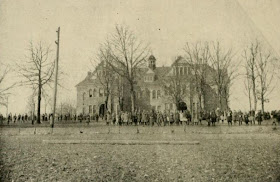

| Graded School c.1902 - Stack & Beasley photo |

|

| Graded School - View from Rear - circa 1914 Heritage Room Photo Collection |

"We had regular curricula, you see. Under the academy, I think, it was more or less left to the headmaster to work these things out. But with the graded schools, as the name implies, they were actually graded and the curricula set up for each grade on a progressive basis. We thought it was much better. We thought that was quite a step forward."